Blog

Chest X-Ray Interpretation

I recently started assisting a cohort at a local university and made this graphic to help them with their interpretation of X-rays. A million things could be added to this however, you have to start somewhere. Like anything else, it can be helpful to systematize your approach. Hope this helps.

Phase Variable Taxonomy

When talking about different modes of ventilation, it is important to be speaking the same language as everyone else. For this purpose, it can be helpful to use a classification system. The one I find to be the most useful in breaking down how ventilator modes work is phase variable taxonomy. It may sound intimidating, but at it’s most fundamental, it is just breaking down the ventilator modes into 3 phases. The trigger phase (what starts the breath), the limit phase (what constrains or limits inspiration without ending it), and the cycle phase (what ends inspiration and begins exhalation). I’ve broken this down into a one page reference guide, as well as several more focused slides to help solidify this concept. Hope this helps!

Pulmonary Vascular Resistance Curve

When treating patients sensitive to changes in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), such as those with right heart failure or pulmonary hypertension, it's crucial to understand how lung volumes affect PVR.

To clarify, we can categorize the pulmonary vasculature into two types: intra-alveolar and extra-alveolar vessels.

Intra-alveolar vessels are found within alveolar ducts and walls, where gas exchange occurs. As the lungs inflate, the capillaries in the alveolar septal walls become compressed, increasing intra-alveolar PVR.

Extra-alveolar vessels, which are connected to lung parenchyma, distend or elongate during lung inflation. An important factor here is hypoxic vasoconstriction: in regions of atelectasis, the lack of oxygen leads to vessel constriction, causing intra-pulmonary shunting. This reduces gas exchange efficiency and raises PVR.

The overall PVR curve follows a U-shape, with the optimal balance occurring at functional residual capacity (FRC). At this point, intra-alveolar vessels are minimally compressed, and extra-alveolar vessels are adequately distended.

Clinical application: For example, when treating a patient with severe pulmonary hypertension, a chest X-ray revealed hyperinflation (10 ribs expanded) and darkened hilar regions. Recognizing that hyperinflation could place the patient at the high end of the PVR curve, we decreased PEEP, which led to an immediate increase in SpO2 from the low 90s to 100%. This allowed us to gradually reduce nitric oxide and FiO2 as well.

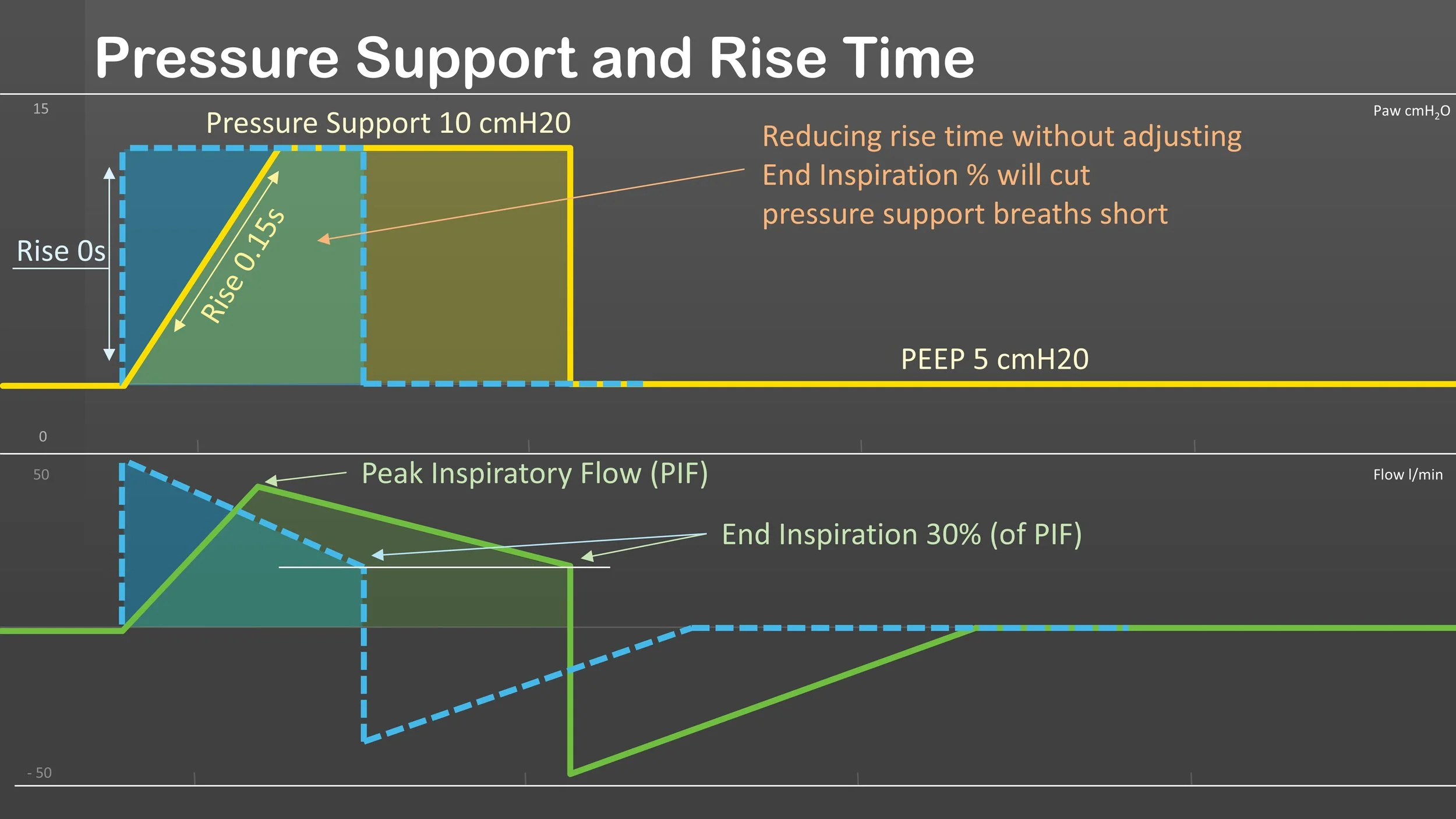

Pressure Support and Rise Time

Rise time is a valuable tool for improving patient synchrony during mechanical ventilation. However, it’s important to remember that on many ventilators, the rise time setting affects both control and pressure support breaths. This becomes especially relevant in modes that combine SIMV and pressure support.

Ventilator Mode Cheat Sheet

In most cases, it is not the mode you choose but how you choose to use it. With that being said, every patient is different, and every mode goes about accomplishing the tasks of ventilation and oxygenation a bit differently. Hope this helps clear up some of the major differences.

“Cycling Down” PRVC

PRVC can become problematic in patients with increased ventilatory demand and respiratory drive (febrile peds, sepsis, DKA, neuro, etc.).

Time Constants

Time Constant = Resistance x Compliance

A time constant is the time it takes for a 63% change in lung volume. Three time constants account for 95% of the volume change. Time constants can be used for inspiration as well as exhalation; however, expiratory time constants tend to be more accurate and useful for determining compliance due to exhalation typically being a passive phase. Increased compliance or resistance leads to longer or shorter time constant values and different lung areas may have varying time constants. This is especially important for patients with obstructive diseases like BPD and COPD.

ABG Interpretation

I’ve frequently seen students and even practitioners struggle with ABG interpretation due to what I believe is the lack of a consistent system.

I like to look at the pH and then systematically classify the CO2 and Bicarbonate as either a driver or compensation mechanism. Once you determine these two things, it becomes much easier to interpret.

This can sometimes be complicated in the setting of mixed/combined pH imbalances, but I will talk about that in another post. I have however included two formulas for CO2 compensation at the bottom of the graphic. I will be posting a video next week breaking down the process of using this sheet. I hope you all will find this useful.